Summary

Resource-rich countries that have limited access to capital and credit, but high needs for infrastructure development, often consider “package deals” to develop their infrastructure in exchange for their natural resources. The resources pledged by the state may include exploration or production rights for oil, gas and minerals, as well as access to land, energy and water resources or the future delivery of extractives commodities. The resources brought by the investor may include loans, grants and infrastructure works, such as railways, roads, ports, power plants, schools and hospitals.

These agreements are often referred to as “infrastructure provisions”, “barter agreements”, “resource financed infrastructure” or “resource-backed loans”. Such agreements may be governed by government-to-government agreements accompanied by complex supporting agreements and involving a number of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or private sector entities.

The terms of these agreements and corresponding value transfers may be complex, opaque and difficult to oversee, making them vulnerable to corruption. In some countries, the values involved may represent a significant amount of the total extractives revenues accruing to government. They may also have an impact on a country’s debt sustainability, in particular during commodity price downturns.

Requirement 4.3 of the EITI Standard requires that these types of infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements be publicly and comprehensively addressed when material, providing a level of detail and transparency commensurate with the disclosure and reconciliation of other payments and revenues streams.

This note provides guidance to multi-stakeholder groups (MSGs) on how to report on such deals as part of EITI implementation, presents a set of examples from implementing countries and outlines opportunities to strengthen the dissemination and use of data.

-

What revenues has the state pledged in exchange for the exploitation of natural resources or infrastructure deals?

-

What is the role played by SOEs in these agreements? What revenues are they collecting?

-

What are the infrastructure works covered by the agreement? For what value? Which government agency is responsible for them? Which companies are executing these works?

-

How are resources exchanged for loans or infrastructure valued? How do commodity price fluctuations affect repayment and broader debt sustainability?

-

What are the terms of the reimbursement of loans to extractive companies in exchange for resources, and are they being followed?

Overview of steps

|

Steps |

key considerations |

examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

Step 2: |

|

|

|

Step 3: |

|

|

|

Step 4: |

|

|

|

Step 5: |

|

|

How to implement Requirement 4.3

Step 1: Agree a definition of infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements

The MSG should agree a definition of infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements that is in line with the minimum required by the EITI Standard. Requirement 4.3 defines infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements as “any agreements, or sets of agreements involving the provision of goods and services (including loans, grants and infrastructure works), in full or partial exchange for oil, gas or mining exploration or production concessions or physical delivery of such commodities.”

The definition should clearly distinguish between arrangements involving the provision goods and services in full or partial exchange for oil, gas or mining exploration or production concessions or physical delivery of such commodities, on the one hand, and those that do not feature such an exchange, on the other.

Types of infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements covered by the definition in Requirement 4.3 include, but are not limited to:

- Agreements providing infrastructure in exchange for mining, oil or gas licenses, whereby an investor pledges the development of infrastructure works in exchange for the granting of prospection, exploration or production licenses or contracts in the mining, oil and gas sectors. This includes cases where extractives licenses or contracts have been awarded contingent on the development of infrastructure in lieu of financial payments to government (e.g. signature bonus). A key test is to consider whether the extractives license would have been awarded in the absence of the provision related to the development of infrastructure for third-party access.

- Agreements providing infrastructure in exchange for future delivery of mineral, oil or gas commodities, whereby an investor pledges the development of infrastructure works in exchange for the future delivery of mineral, oil and gas commodities, e.g. an oil and gas company funds, develops and transfers a power plant to the government in exchange for deliveries of crude oil in kind. Such agreements are different from infrastructure works undertaken by the company as part of its own operations – even if the company agrees that the infrastructure can be used for other purposes, (e.g. roads, a port or energy plant – see examples below of agreements that are not considered within the scope of Requirement 4.3).

- Agreements providing loans in exchange for future delivery of minerals, oil and gas commoditiesHideThe World Bank defines resource-financed infrastructure, a type of barter-type arrangement, as follows: “Under a resource-financed infrastructure arrangement, a loan for current infrastructure construction is securitized against the net present value of a future revenue stream from oil or mineral extraction, adjusted for risk. Loan disbursements for infrastructure construction usually start shortly after a joint infrastructure-resource extraction contract is signed, and are paid directly to the construction company to cover construction costs. The revenues for paying down the loan, which are disbursed directly from the oil and mining company to the financing institutions, often begin a decade or more later, after initial capital investments for the extractive project have been recovered. The grace period for the infrastructure loan thus depends on how long it takes to build the mine or develop the oil field, on the size of the initial investment, and on its rate of return.” World Bank (2014), Resource financed infrastructure: a discussion on a new form of infrastructure financing, p. 4., whereby an investor provides loans to a government in exchange for future delivery of mineral, oil or gas commodities. This loan is to be spent on investments external to the concession, meaning that they do not contribute to project finance or carried equity. An example of this is a commodity trader that provides sovereign loans (including pre-financing agreements and resource-backed loans) in exchange for future delivery of crude oil at set terms and for a set period.

- Agreements involving the exchange of mineral, oil and gas commodities, whereby the state’s in-kind revenues of mineral, oil and gas commodities are exchanged for other types of commodities. These include swaps, refined product exchange agreements and offshore processing agreements.

The following types of arrangements are typically not considered infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements:

-

Amortisation of infrastructure investments over future tax liabilities. Common in many countries, these types of arrangements consist of tax incentives for companies undertaking infrastructure investment. For instance, a company could deduct the cost of its infrastructure investments (up to a set level) from its tax liabilities to government. However, the granting of those companies’ mining, oil and gas licenses is not contingent on the companies availing themselves of the tax offset for their infrastructure investments. Several EITI implementing countries have nonetheless included disclosure of these tax credits in the scope of their EITI reporting as MSGs may decide that such information is of public interest.

-

Cost recovery of infrastructure investments. These types of arrangements, common in many petroleum producing countries in particular, consist of companies recovering the cost of their infrastructure investments from government under ”cost recovery” provisions of their production-sharing contracts.

Pitfalls of collateralised financing

According to the International Monetary Fund, “Collateralized financing can be harmful in two key circumstances: Foremost, when a transaction does not produce an asset or revenue stream that can be used for repayment, and the volume of the transaction raises broader financing or debt distress concerns. Second, when the transaction does not involve adequate transparency or disclosure (and would thus impede the ability of future creditors to correctly assess risks and lend sustainably, contributing to future problems).” The MSG could consider whether to outline risks related to collateralised financing linked to extractive resources in light of the national context.

Step 2: Identify existing infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements

In establishing the scope of EITI reporting, the MSG needs to determine whether the government or government-related entities (including SOEs) have entered into any agreements which meet the agreed definition of infrastructure provisions and barter agreements.

The MSG might task a technical working group, the national secretariat or an external consultant to examine whether any such deals are in force or have been discussed, through a review of publicly-available sources and consultations with government, industry and civil society actors. The findings from this work should be documented (e.g. in MSG minutes or a scoping report). The MSG may also wish to consider whether the disclosure of agreements related to the exploitation of oil, gas and minerals (Requirement 2.4) is relevant in the context of any infrastructure provision or barter arrangements.

The following examples constitute infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements in accordance with Requirement 4.3:

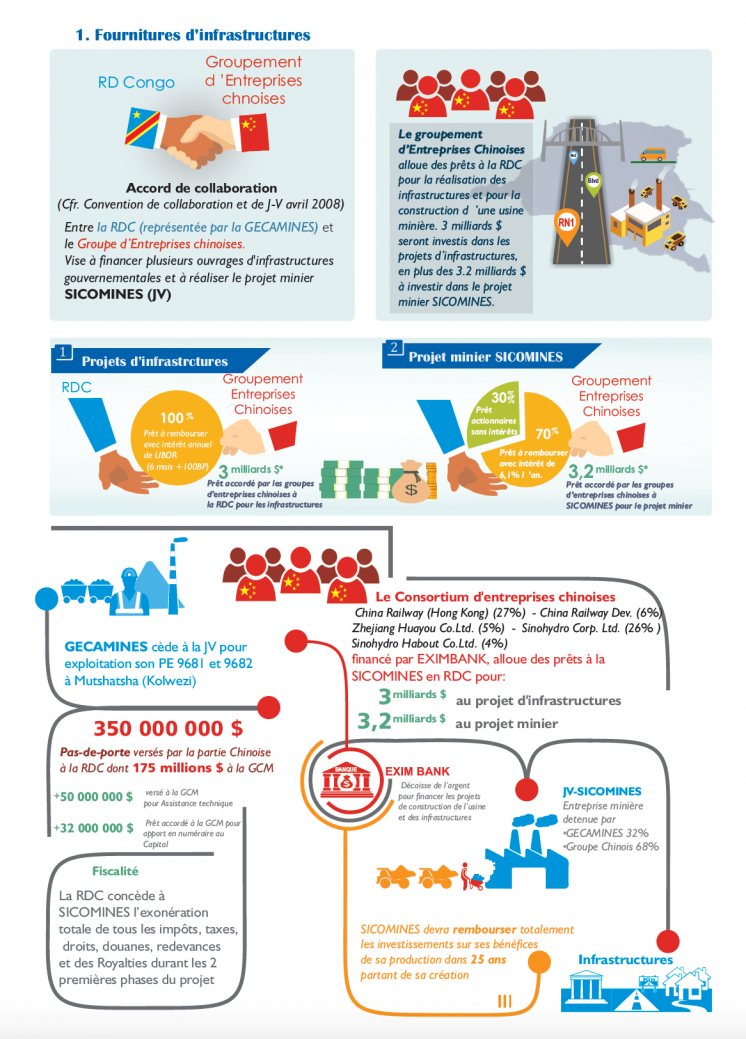

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Infrastructure agreement

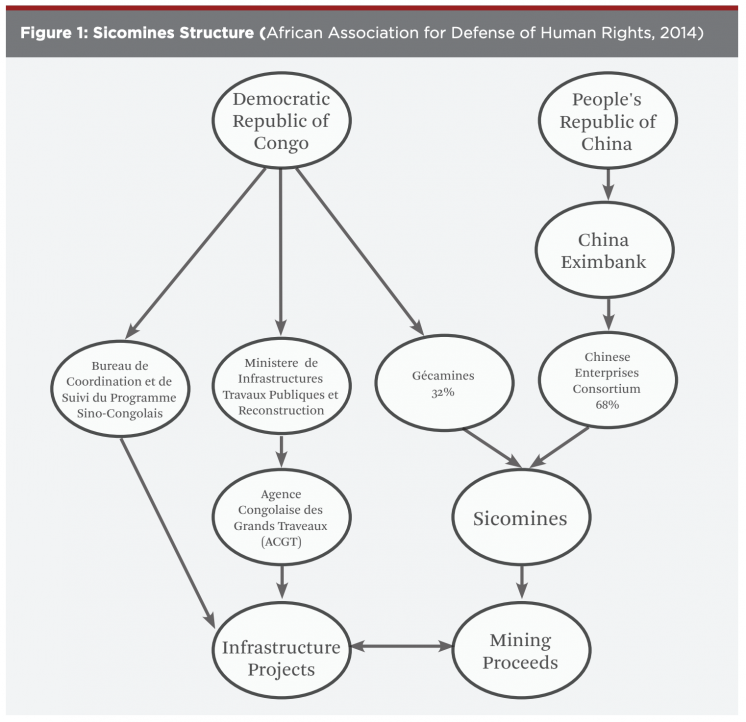

The Sino-Congolese Cooperation Agreement is an inter-governmental agreement involving the DRC’s state-owned mining company, Gécamines, and a consortium of Chinese enterprises (CREC3 and Sinohydro). The agreement established a joint venture, SICOMINES, which received mining rights in exchange for the development of infrastructure such as roads and hospitals.

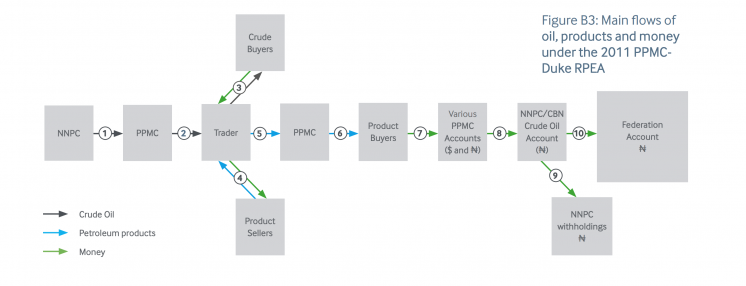

Nigeria: Swaps with commodity traders

Nigeria’s Petroleum Products Marketing Company (PPMC) has engaged in swaps with traders, exchanging crude oil for refined petroleum products. The swaps are called Refined Products Exchange Agreements (RPEA), or more recently known as Direct Sale Direct Purchases (DSDP). The below example illustrates a swap with the commodity trading company Duke Oil.

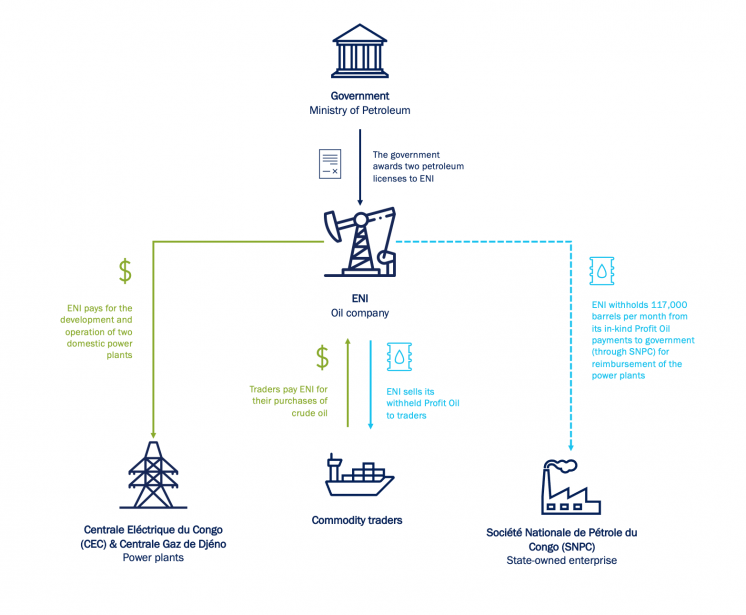

Republic of the Congo: Infrastructure for mineral rights and commodities

The oil and gas company ENI Congo has been compensated for the cost of development and operation of two power plants in Pointe Noire with the award of two oil and gas licenses and permission to deduct 117,000 barrels a month from its profit oil payments to government over a period of 10 years. This is deducted to reimburse the costs of developing and operating the two power plants in Pointe Noire. The subsidiary then sells this crude oil to trading companies.

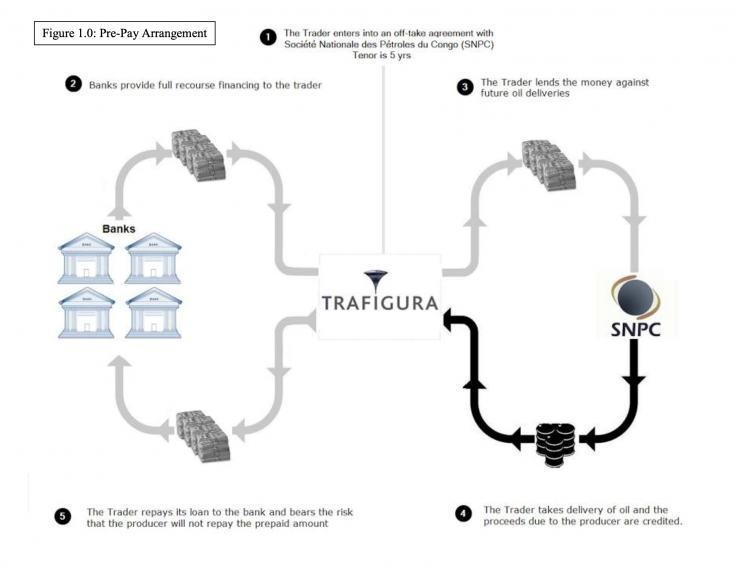

Republic of the Congo: Loans in exchange for crude oil

Commodity traders like Trafigura have extended loans to governments in the Republic of the Congo, securitised against the delivery of crude oil.

The following are examples of agreements that are not considered infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements in accordance with Requirement 4.3, but where MSGs have decided to disclose pertinent information about the agreement:

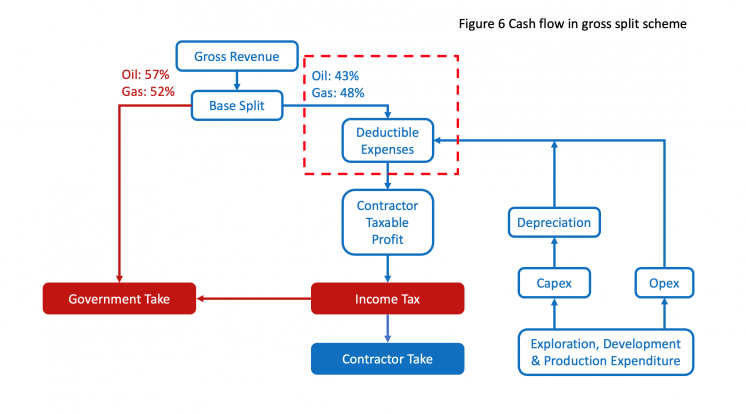

Indonesia: Infrastructure cost recovery

Oil and gas companies in Indonesia were previously able to recover the cost of infrastructure investments from the government through cost recovery arrangements, these being common provisions of Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs). License awards or delivery of mineral, oil or gas commodities were not contingent on the infrastructure investment, and were thus not considered a barter-type infrastructure provision according to the EITI Standard.

Cost-recoverable infrastructure has since been abandoned following the introduction of the new gross split system through the 2017 enactment of the Indonesian Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR) Regulation No. 8.

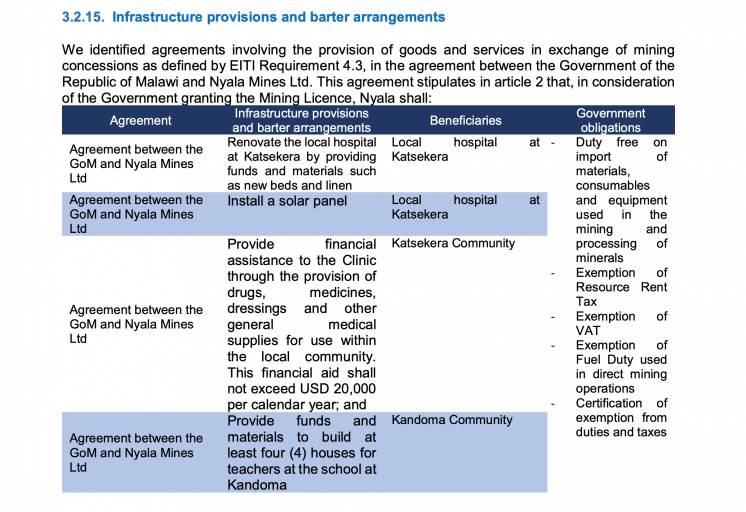

Malawi: Tax exemptions

Malawi’s 2015-2016 EITI Report describes a Development Agreement between the government and Nyala Mines including infrastructure provisions and social expenditures in exchange of several tax exemptions. However, the exemptions were not provided in full or partial exchange for extractives licenses or delivery of mineral, oil or gas commodities. Therefore, these are not considered a barter-type infrastructure provision according to the EITI Standard.

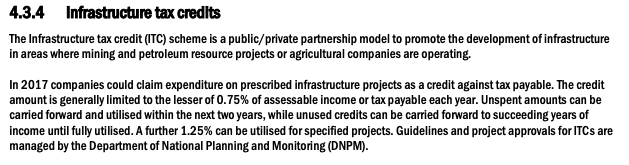

Papua New Guinea: Infrastructure tax credits

In Papua New Guinea, companies can deduct the cost of infrastructure investments against future tax liabilities to government. Award of licenses or delivery of mineral, oil or gas commodities is not contingent on the infrastructure investment, and is thus not considered a barter-type infrastructure provision according to the EITI Standard.

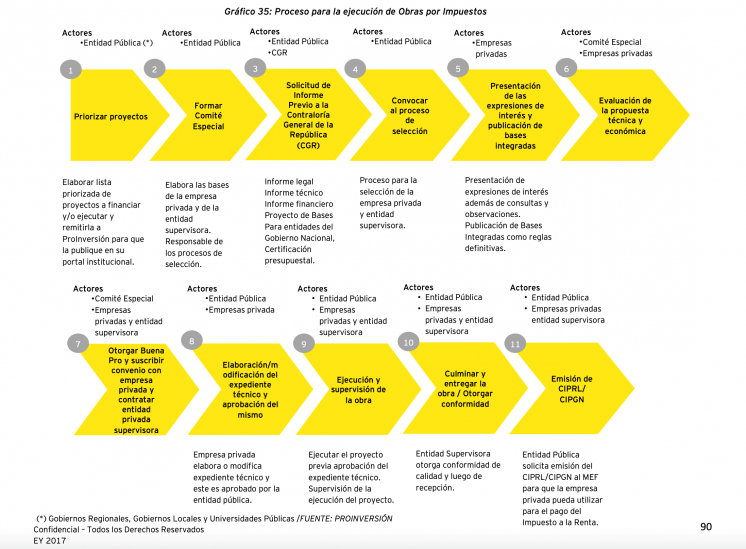

Peru: “Works for Taxes” regime

Peru’s “Works for Taxes” (WxT) regime is a method for all companies to offset Corporate Income Tax against the value of infrastructure projects. Companies have the option to pay this tax in-kind based on pre-approved conditions through the execution of public work projects, instead of a cash settlement. The companies are not required to undertake such public works in full or partial exchange for oil, gas or mining exploration or production concessions. Therefore, these are not considered a barter-type infrastructure provision according to the EITI Standard.

Step 3: Develop a more detailed understanding of the agreements

Where the MSG has established that infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements are material, additional consideration is needed to gain a full understanding of these agreements. Findings from this work should be documented through EITI reporting.

For each agreement or sets of agreements, the MSG needs to clarify:

- The terms of the relevant agreements and contracts

The MSG should gain access to and publicly disclose the key terms of such agreements. The key terms could include the timeframe for the agreement, the resources pledged by the state, the value of the balancing benefit stream (e.g. infrastructure works), the interest rate and reimbursement modalities of relevant loans (where applicable).

Where contracts are not available, the MSG should ensure that the government and relevant parties to the agreement provides a summary of the key terms of all mining, oil and gas contracts related to infrastructure provisions or barter arrangements.

Measuring and mitigating risks related to reimbursement

The MSG could consider whether the disclosed information should specify whether down payments start once the resource asset is operational, or only after the resource investment is paid down and the asset is generating profits. This distinction affects the distribution of risks in the long term, and whether the borrower or the lender assume risks related to delays in the completion of the extractive project.

- The parties involved

The MSG should map the relevant actors to the signature, implementation and monitoring of the agreement. These may include: joint-ventures arising from the contracts and the respective partners; SOEs contracting on behalf of the government; government agencies monitoring the implementation of the agreement; financial institutions providing loans for infrastructure development; and companies building the infrastructure.

Côte d’Ivoire: Swap agreements

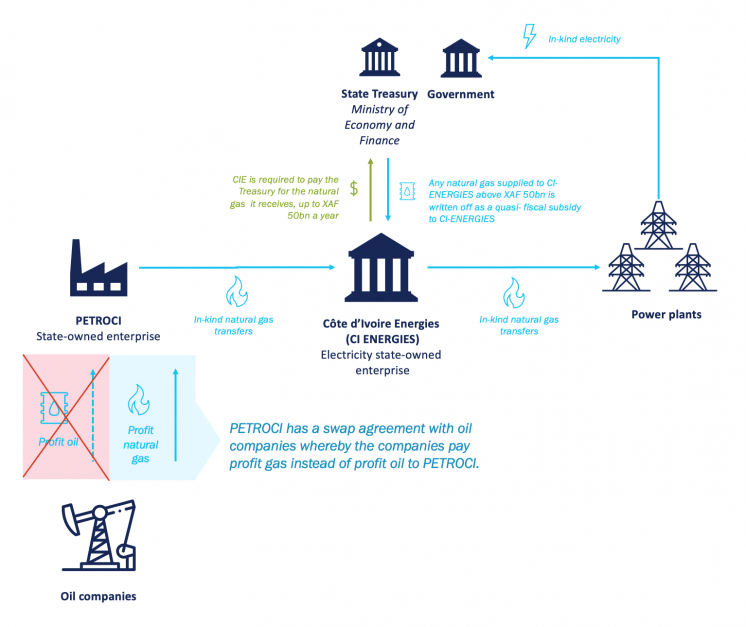

Côte d’Ivoire’s oil and gas sector is geared towards domestic electricity generation. Oil and gas companies pay profit gas to the government through a swap with the national oil company PETROCI, in lieu of profit oil. PETROCI also has an agreement with the domestic power plants to supply natural gas, which is paid for in part by the provision of electricity to the government. The cost of natural gas in excess of the electricity supplied must be paid for in cash (up to 50 billion CFA francs).

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Parties involved in the SICOMINES agreement

The joint venture SICOMINES is registered in the Democratic Republic of the Congo with a 32% stake for the state-owned mining company Gécamines and a 68% stake for a Chinese consortium. Although not a party in the contract, China Exim Bank plays an important role as it financed infrastructure projects and development of the mining project itself. The Agence Congolaise des Grands Travaux is the government agency responsible for the development of the infrastructure, with the Bureau de Coordination et de Suivi du Programme Sino-Congolais in charge of overseeing the infrastructure works and revenue flows.

- The resources which have been pledged by the government

Such resources can include exploration and production licenses issued by the state, tax exemptions, loan repayment programs and loan guarantees.

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Mineral rights awarded as part of the infrastructure agreement

The joint venture SICOMINES was awarded rights to several mining production licenses. The company is entitled to profits from these mining projects for the reimbursement of a certain share of costs for the mining investment and infrastructure categorised as “urgent”. The state has guaranteed the reserves associated with the mining rights, a stable fiscal regime for the duration of the project, and the non-nationalisation of SICOMINES.

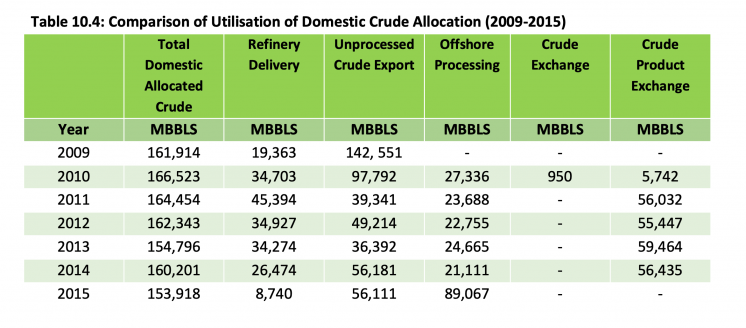

Nigeria: Exchange for crude oil for refined petroleum

The Nigerian government provided crude oil to commodity trading companies in exchange refined petroleum products. Under the “Crude Product Exchange”, crude oil was exchanged for refined petroleum products of any origin. In the “Offshore Processing” agreement, the petroleum product supplied by the traders were supposed to be Nigerian crude that was refined offshore and re-imported to Nigeria.

- The commitments made by the counter-party, whether a government or one or more extractive company(ies) and their affiliates over the life of the project

Such commitments can include infrastructure projects, investments, signature bonuses and other applicable benefit streams.

Measuring and mitigating risks related to construction contracts

The distribution of development, construction and operational risks within the contracts should reflect accepted practice for infrastructure. Depending on context and relevance, MSGs could consider questions to mitigate governance risks such as: Do the terms of the agreement identify the responsible party if there are cost overruns or delays? Is the borrower free to select the construction companies, or are specific construction firms imposed by the lender? Information addressing these questions may help stakeholders understand the terms of the construction contract, distribution of risk and implications for the government.

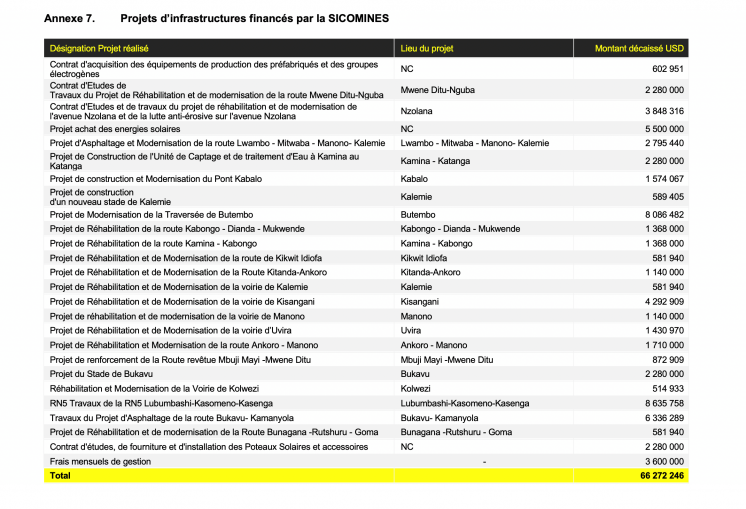

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Infrastructure works

The table below shows ongoing and completed infrastructure works carried out as part of the SICOMINES agreement, and corresponding amounts disbursed in 2016.

Republic of the Congo: Infrastructure for mineral rights and commodities

ENI Congo funded, developed and operated two power plants in Pointe Noire, the 50MW Centrale Gaz de Djéno and the 300MW Centrale Eléctrique du Congo until 2018. The cost of development and operation of the two power plants has not yet been publicly disclosed, pending completion of an audit.

- What mechanisms have been put in place to track, on a continuing basis, the value transfers that are taking place, and the value of the balancing benefit stream

Côte d’Ivoire: Oversight of gas-to-electricity arrangements

The government has established a tripartite committee to oversee the gas-to-electricity arrangements, consisting of the Ministries of Finance and Petroleum, PETROCI and CI Energies to determine valuations of natural gas and electricity supplied. Similar reconciliation meetings take place related to the Profit Oil for Profit Gas swaps on a per-contract basis between the Ministry of Energy, PETROCI and three producing oil and gas companies.

Nigeria: Oversight of swap-type agreements

The Petroleum Products Marketing Company (PPMC) has oversight of the implementation of swap-type arrangements, while the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation’s (NNPC) Crude Oil Marketing Department (COMD) handles deliveries of crude oil as part of these agreements.

Step 4: Establish the reporting procedures

Where infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements are material, the MSG is required to develop a reporting process with a view to achieving a level of transparency at least commensurate with other payments and revenue streams. The MSG might wish to refer to Requirement 4.1.b) of the EITI Standard with regard to the approach to materiality.

In designing reporting templates, the MSG can consider the following information and data points:

- A list of mining, oil or gas projects where mineral or hydrocarbon extraction is contingent on public infrastructure provision, or other barter-type arrangements; and/or a list of agreements where loans, grants or the provision of mining, oil or gas commodities is contingent on deliveries of mining, oil or gas commodities;

- A list of the parties involved in each agreementHideFor bilateral financings, the the Institute of International Finance (IFF)’s Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency encourages disclosures of the lender at signing for bilateral financings. For syndicated financings, the principles recommend disclosures of the mandated lead arrangers and the facility agent, as well as any applicable agent/trustee/transaction intermediary. ;

- A description of the key termsHideThe IIF’s Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency recommends disclosures of the amount which can be borrowed/raised and details of disbursement period; applicable currency or currencies; repayment or maturity profile (including any puts or calls where applicable); and interest rate (or commercial equivalent)., including the resources pledged by the government and companies;

- An overview of the status of implementation of each agreement, including whether they have been renegotiated and how renegotiations have modified the termsHideThe IIF’s Voluntary Principles for Debt Transparency recommends that where the amount which can be borrowed, the interest rate or the repayment profile of a financial transaction is amended or varied, the amendments or variations should be disclosed.;

- A declaration from the relevant companies regarding the value involved in, transferred and outstanding under these projects during the reporting period;

- A declaration from the relevant government agencies regarding the value involved in, transferred and outstanding under these projects during the reporting period;

- Any other information as agreed by the MSG regarding the implementation of these projects; and, where available,

- Valuations provided by independent persons of the value involved in, transferred and outstanding under specific clauses of the agreement(s).

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Production and loan reimbursements

The reporting template below for SICOMINES tracks production and loan reimbursements, including the value of outstanding debt at the end of the year covered.

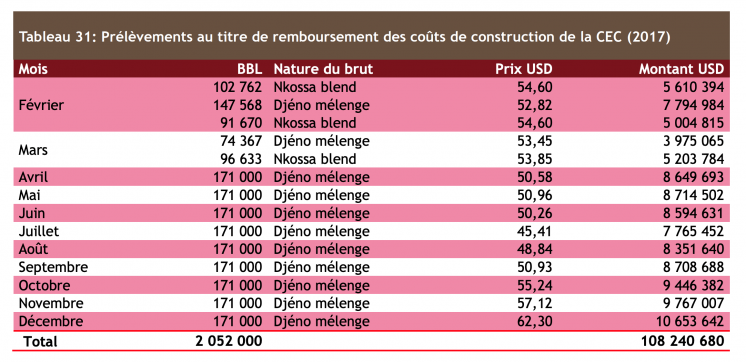

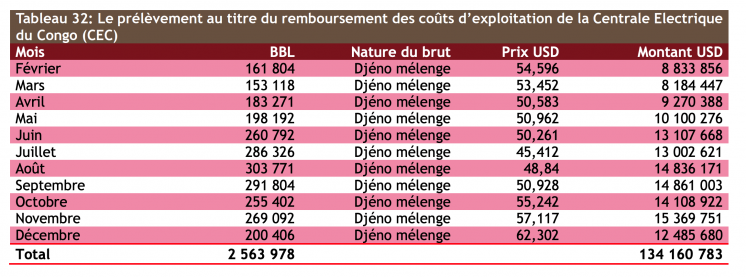

Republic of the Congo: Infrastructure reimbursements

The Republic of the Congo’s 2017 EITI Report provides the volumes and values of monthly crude oil liftings (deductions from profit oil payments to the state) by ENI in reimbursement of the development and operational costs of the CEC power plant. The costs of developing and operating the power plant are however not disclosed.

Step 5: Establishing a mechanism for data quality assurance

The MSG should ensure that an assessment of the comprehensiveness and reliability of information related infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements is disclosed in accordance with Requirement 4.9.

The MSG could also consider agreeing recommendations on opportunities to further enhance transparency in the governance of these agreements.

The MSG should consider the underlying audit and assurance practices related to the sources of information on these agreements. Where comprehensive and reliable information is not available, the MSG should agree an approach for ensuring the reliability of information on these agreements in its EITI reporting, which could include reconciliation of reporting by the different parties to the transaction(s) and/or reference to audited financial statements related to these transactions.

Auditing transactions related to the loans

If there are concerns about the oversight of any infrastructure provisions and barter arrangements or the quality of information, the MSG could consider whether audits have been undertaken and what are the accounting practices related to the agreements. If a single account has been established to manage funds related to such agreements, it will allow stakeholders to more easily account for and audit transactions. If such an account is set up as a special purpose vehicle in a jurisdiction with strong rules for tax transparency, this could further enhance transparency and accountability.

Further resources

-

Natural Resource Governance Institute (2020), Resource-Backed Loans: Pitfalls and Potential

-

IMF (2020), Collateralized Transactions: Key Considerations for Public Lenders and Borrowers

-

Institute of International Finance (2019), Voluntary Principles For Debt Transparency

-

World Bank (2014), Resource Financed Infrastructure: A Discussion on a New Form of Infrastructure Financing

Related content