Summary

Contract disclosure is a vital aspect of natural resource governance. It can be a powerful tool for mitigating corruption, mobilising revenues, building trust and negotiating fair deals. By shedding light on the rules and terms that govern extractives projects, contract transparency empowers citizens to assess whether they are getting a good deal for their resources.

Publication of contracts gives visibility on how much revenue is expected to flow to national and subnational governments and other stipulations related to environmental and social obligations. Access to this information enables citizens to hold companies and governments to account for non-compliance. In addition, understanding the terms of agreements is critical to inform approaches to the energy transition, including the distribution of risk and reward through the legal and fiscal terms of production.

Contract disclosure can also strengthen systems and regulation in the sector. It helps governments operate effectively by providing agencies with the same information on the monetary and non-monetary obligations of companies. For industry, contract disclosure can mitigate reputational risks, build trust and strengthen a company’s social license to operate.

Requirement 2.4 of the EITI Standard requires that countries fully disclose any contracts and licenses that are granted, entered into or amended from 1 January 2021. This requirement aims to shed light on the deals governing extractive operations so that citizens are better equipped to understand the expected contribution of extractive projects to their country.

This note explains the requirements on contract transparency and key concepts related to contract disclosure. It provides detailed guidance to multi-stakeholder groups (MSGs) on approaches to disclosing contracts, including practical steps and ways of addressing barriers. This draws on the EITI Board’s clarification of Requirement 2.4 and supplements the EITI’s policy brief on contract transparency.

For a checklist of suggested activities to integrate contract disclosure into EITI work plans, see Annexe A.

- Which companies are operating in the country and what are the terms on which their oil, gas and mining activities take place?

- Are companies complying with their legal and fiscal obligations? Is the government effectively enforcing the rules?

- What subsidies and tax incentives are being awarded to extractive companies? Do companies benefit from stabilisation clauses?

- What social, environmental and health and safety obligations are placed on companies to protect communities and the environment? Do contracts include local content provisions, community consultation requirements, and community development agreements?

- How are risk and reward distributed between the state and the private sector?

Communities stand to benefit from contract transparency. They will be able to see how much revenue is flowing from extractive companies to their countries. Any subsidies and tax incentives awarded to companies will be in plain view. Stakeholders will be able to monitor obligations placed on companies to the environment, to make social payments, and to provide local employment and use local suppliers.

Overview of steps

|

Steps |

Key considerations |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Step 1: |

|

|

|

Step 2: |

|

|

|

Step 3: |

|

|

|

Step 4: |

|

|

|

Step 5: |

|

|

Key concepts

Contracts and licenses

In most countries, citizens own oil, gas and mineral resources. When governments, as representatives of the nation, decide to develop natural resources, they can enter into agreements with companies to give them the right to exploit the natural resources in exchange for a share of the profits. These agreements go by many names, including contracts, licenses, concessions or permits. In this document, references to contracts also include licenses and other types of agreement unless distinguished explicitly.

Requirement 2.4.d) defines contracts as the full text of any agreement providing the terms for exploitation of oil, gas and minerals. Requirement 2.4.e) defines licenses as the full text of any license, lease, title or permit by which the government confers on a company or individual rights to exploit oil, gas and/or mineral resources. Each country has different types of agreements. Broadly, they could be categorised into those where the terms are negotiated on a per contract basis, and those where the stipulations are uniform for all contracts and companies.

EITI Requirement 2.4 applies to all types of contracts regardless of the type or nomenclature used in the country. It equally applies to countries that follow the license regime. The test to determine what to disclose under Requirement 2.4 is to examine whether the agreement contains the obligations or conditions agreed by the companies with the government under which the right to exploit or extract oil, gas and minerals in the country has been granted.

Types of agreements

There are various types of agreements in different countries. The more common types of agreement are production sharing agreements (PSA) where the state contracts with a company to provide financial and technical resources and the company is granted an exclusive right to explore and produce oil and gas within a defined contract area. Under PSAs, companies are entitled to a portion of the commodity as compensation. The state retains ownership of the commodities subject to the production sharing scheme with the company.

A few jurisdictions still use concessions where the company is typically granted proprietary rights over the contract area and complete ownership over production, subject to the payment of a royalty and income tax.

Other countries issue licenses, where stipulations are generally embedded in legislation and do not vary from contract to contract (e.g. Germany, Norway, UK, Zambia).

Other types of agreements have also emerged, combining various stipulations listed above.

Terms attached to the exploitation of oil, gas and minerals

When determining which contracts and licenses contain the terms attached to the exploitation of oil, gas and minerals (and thus are eligible for publication), MSGs could be guided by matters covered by the EITI Standard. This can include fiscal terms (Requirement 2.1), state participation (2.6), exploration (3.1), production (3.2), infrastructure and barter agreements (4.3), transportation revenues (4.4), transactions related to SOEs (4.5), subnational payments (4.6) and social and environmental expenditures (6.1). They may also be guided by encouragements relating to the term of the sale of the state’s share of production (4.2.b) and environmental impact (6.4.b).

Full text of contracts and licenses

The EITI Standard requires that all stipulations in a contract be disclosed without exception. Where there are redactions or omissions of certain texts due to commercial sensitivity or restrictions on confidentiality, the country will not meet the EITI’s requirements on full contract disclosure (see Step 4 and 5). The contents of extractive contracts vary, but they might typically include the following:

- Preliminary stipulations (e.g. date of execution or effectivity, parties to the contract, considerations for entering into the contract, definition of terms);

- Fiscal terms (e.g. royalties, fees, production sharing);

- Non-fiscal terms (e.g. social obligations, environmental obligations, rehabilitation or decommissioning plans);

- Administrative provisions (e.g. reporting obligations, inspection rights, force majeure clauses, stabilisations clauses, venue of litigation/arbitration of disputes).

Because contracts contain detailed and related terms, publishing the full-text documents without redactions or omissions is important to avoid misrepresentation, misunderstanding and mistrust that may arise from incomplete or inaccurate summaries of contract documents.

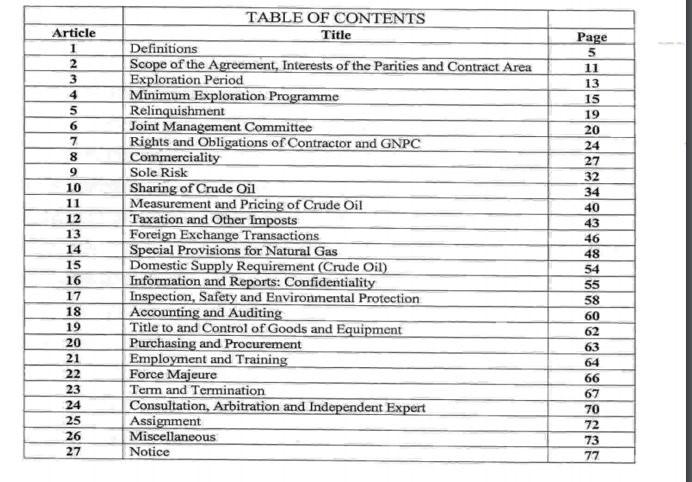

Ghana: Contractual stipulations

The disclosure of a petroleum agreement between the Government of Ghana and Amerada Hess Ghana Limited provides contractual stipulations in full.

Annexes, addenda and riders

These refer to documents that supplement or provide details to the stipulations in the main contract. Some contracts explicitly refer to or append the additional documents that are considered integral parts of the contract. These vary for each contract, but typically include site maps or contract area, accounting procedures, details of project cycle, takeover procedures, management procedures, guarantees and feasibility studies.

When it is unclear which additional documents are considered as annexes, riders or addenda, the MSG should ask the parties to the contract to disclose them in order to fully adhere to EITI Requirement 2.4 (see Step 1).

Alteration or amendment

This refers to revisions in contractual stipulations, including changes in parties to the contract. The EITI Standard does not distinguish between substantial or minor amendments and requires the disclosure of full text of any alteration or amendment.

Policy on contract disclosure

In some countries, government policies on contract disclosure are embodied in constitutional provisions, legislation, government regulations, or to public commitments made by key government officials (typically ministerial level or higher). It is important for the MSG to examine the official policy and actual practice, and to document any inconsistencies.

How to implement Requirement 2.4

Step 1: Discuss objectives for contract disclosure and agree on an action plan

It is important for all stakeholders in the MSG to appreciate how contract disclosure could benefit their respective constituencies. In agreeing the objectives, MSGs could consider links to broader reforms related to mitigating corruption, increasing tax revenues and monitoring environmental and social obligations.

Examples of objectives could include:

- Understanding the fiscal terms for each agreement, and how they can inform better projections of the timing and volume of national and subnational government revenues;

- Enabling citizens and government oversight bodies to monitor compliance with legal obligations in contracts;

- Enabling citizens and oversight bodies to understand the state’s legal rights, obligations and limitations in the contract, including around cost auditing timing and rights, stabilisation clauses and their scope, and requirements for allocations of revenues to local governments or local communities;

- Addressing reputational risks for companies;

- Ensuring consistent access to contractual precedents as references for future negotiations;

- Understanding how contract terms have an impact on broader strategy goals, including energy transition plans;

- Setting expectations among government agencies and the public on the timing and volume of government revenues from key projects.

These objectives should guide MSGs in agreeing on activities in their work plans. According to Requirement 2.4, MSGs are expected to agree and publish a plan for disclosing contracts with a clear time frame for implementation and addressing any barriers to comprehensive disclosure. This plan will be integrated into work plans covering 2020 onwards. All work plans are required to be fully costed, indicating the staff and funding needed to carry out these activities, as well as plans to address funding gaps.

MSGs are also expected to identify measurable targets within a specific timeframe to carry out these activities. MSGs should obtain clarity on what reforms could be implemented immediately, what long-term reforms are needed (e.g. legal amendments), and what practical steps should be taken to implement such reforms.

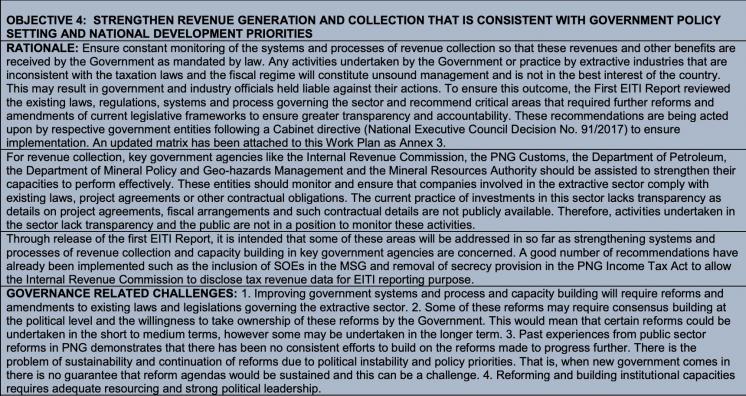

Papua New Guinea: 2021 work plan objectives

PNG’s 2021 work plan explains how the MSG intends to use contract disclosure to strengthen revenue collection by enabling government agencies (including tax authorities and regulatory bodies) to monitor compliance with existing laws and contractual obligations.

Step 2: Engage key stakeholders and build capacity

Full contract transparency requires the commitment of high-level officials and technical staff in government and industry. MSGs are expected to identify challenges in securing commitment and to adopt strategies on how to address them, for example through a stakeholder engagement plan. Ensuring that contract disclosure contributes to government and companies’ own objectives is key. Civil society can also play an active role in explaining the importance of contract transparency to all constituencies, including drawing attention to specific terms or contracts that should be publicly available.

In engaging key stakeholders, MSGs could consider identifying champions of contract transparency, potential saboteurs, effective communicators (including media), drivers of related reforms (such as anti-corruption actors), technical assistance providers, and responsible parties in government (e.g. contract repositories). Legal advisers for government and companies also often play a key role in discussions on legal barriers. When engaging with government agencies, MSGs might wish to ensure that they are working with all the agencies that participate in awarding and monitoring contracts, which can be hosted in different ministries.

Contract transparency should not be an end in itself, but should contribute to better governance of the extractive sector. Key to this is for stakeholders to understand contracts and develop skills to analyse contractual stipulations. To this end, MSGs could consider identifying capacity building activities to meet its objectives for contract disclosure. For example, if the objective is to strengthen revenue collection, MSGs could consider organising workshops on understanding the fiscal terms of contracts.

Cameroon: Stakeholder engagement in contract disclosure

In December 2019, the Cameroon EITI MSG established a working group on contract transparency. The working group was tasked with drafting a work plan to address obstacles to disclosures and make proposals for new regulation in line with Requirement 2.4 of the EITI Standard. The working group’s draft work plan included a roundtable with government, company and civil society representatives to strengthen commitment for contract transparency. It also included regular capacity-building activities for key stalkeholders to effectively monitor progress on disclosures.

Madagascar: Building stakeholder capacity to identify solutions for contract disclosure

Despite several mining contracts being publicly available, Madagascar does not have an explicit government policy on contract transparency. EITI reporting has highlighted the existence of confidentiality clauses in model PSAs in the oil and gas sector. It recommended that the government and industry associations work together to disclose all extractive contracts.

In response to demand from the EITI Madagascar MSG, the International Secretariat facilitated a workshop with MSG members in December 2020 on best practices in EITI implementing countries in addressing obstacles to contract transparency. The MSG discussed how to formulate government policy and adopt the adequate legal and regulatory framework. The MSG reviewed best practices from other EITI implementing countries on online disclosure platforms.

Step 3: Secure and publish a list of all active contracts in the country

Countries are required to publish a list of all active contracts in the country, including those executed before 1 January 2021 (Requirement 2.4.c.ii). The MSG should agree on what constitutes extractive contracts in the country given the different nomenclatures and a determination of relevant annexes.

It is suggested that MSGs proceed as follows:

- Conduct a scoping exercise. The scope of the exercise should include exploitation and exploration contracts, annexes, amendments, addenda or riders.

Agree on considerations for materiality of exploration contracts. This could include:- Agree on a list of active contracts and licenses, including exploration contracts. MSGs should request a list of all active contracts in the country from the government body that granted the right to explore or exploit. Industry parties could be asked to confirm the information provided. For countries that follow license regimes, MSGs are still required to include all issued licenses in this list, even if these licenses have standard or uniform stipulations.

Other sources could also be consulted. For example, some jurisdictions require extractive contracts to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission or with parliament, or for these contracts to be published in national gazettes. Some companies also disclose contracts on their websites. The MSG could draw on these sources to cross-check the list provided by the government agency that executed the agreement. The MSG may also wish to consult resourcecontracts.org, a global repository with around 2,400 extractive contracts, including summaries of contract terms.

Scoping exploration contracts

All exploration contracts, regardless of materiality, should be included in the list of active contracts that implementing countries must provide under Requirement 2.4.c.ii. With respect to their publication, MSGs are given the discretion to select which exploration contracts are considered material and should be disclosed. However, where the terms of exploration are bundled with exploitation contracts (as is commonly the case in the petroleum industry), the requirement applies even if the project is in the exploration phase.

Determining the materiality of exploration contracts could involve the following steps:- Agree on considerations for materiality of exploration contracts. This could include:

- Whether there are material payments stipulated in these exploration contracts. The MSG could opt to use the same threshold it uses for material payments in EITI reporting.

- Whether the exploration contract is granted to a material company as determined by the MSG for EITI reporting purposes.

- Whether exploration contracts contain non-fiscal obligationsHideThis could include time limits for exploration, minimum work obligations over a certain period, extent of state supervision, terms of relinquishment, public financial obligations associated with SOE equity holding in exploration projects, social and environmental expenditures, as well as obligations for monitoring environmental impact at the exploration stage, etc. that the public would be interested to know.

-

Consider other factors such as demand from stakeholders and the administrative burden of disclosing these contracts.

- Agree on considerations for materiality of exploration contracts. This could include:

- Determine relevant annexes, addenda or riders. The scoping exercise should determine what annexes and associated documents should be disclosed for each contract or license in the list. Where there are clear rules on what should be considered as an annex, addendum or rider as specified either by law or by a specific contract, the country should ensure that such annexes, addenda or riders are disclosed. The MSG would need to examine further what additional documents are needed to fully explain the terms attached to the rights granted to the company. These discussions should be documented by the MSG through meeting minutes or scoping studies, including references to specific rules on what constitutes an annex, addendum or rider to ensure consistency with applicable law.

- Indicate in the list which contracts are publicly available, and which are not. For all published contracts and licenses, the list should include a reference or link to the location where the contract or license is published (Requirement 2.4.c.ii). The MSG could encourage the relevant ministry to systematically disclose the list of active contracts with corresponding links.

- Agree on a list of active contracts and licenses, including exploration contracts. MSGs should request a list of all active contracts in the country from the government body that granted the right to explore or exploit. Industry parties could be asked to confirm the information provided. For countries that follow license regimes, MSGs are still required to include all issued licenses in this list, even if these licenses have standard or uniform stipulations.

- Identify ongoing and future bid and contract negotiations. To keep track of new contracts, government agencies that conduct bidding or negotiations are encouraged to routinely publish information on these bidding rounds on their websites. Where feasible, they are encouraged to inform the MSG on the status of these processes. Where this information is publicly available, national secretariats could also monitor them.

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Mapping contracts to ensure comprehensiveness

In 2011, the DRC government established a legal basis for contract disclosure through the adoption of a decree. Yet while many contracts have been disclosed through a government portal, EITI stakeholders have identified missing documents. They have since been working closely with relevant government agencies and state-owned enterprises such as GÉCAMINES to disclose them.

Ensuring the comprehensiveness of contracts is a priority for the MSG. It examined whether all existing contracts have been fully disclosed and whether disclosures include the full text of the agreements. Preliminary analysis showed that the disclosed document for the large-scale copper Deziwa project was a framework agreement that did not fully include revenue flows. In 2020, the MSG commissioned a study to assess the comprehensiveness of disclosures to date, identify missing documents and help establish a system that ensures timely and comprehensive disclosures in accordance with the law.

Step 4: Understand the current state of contract disclosure and develop a plan to address barriers

- The MSG should first seek to understand current practices on contract disclosure. This step is recommended before the MSG commissions a legal review. The MSG could then identify practical or legal barriers to disclosure and how to address them. The MSG could consider:

- Determining which contracts are already being disclosed;

- Identifying which contracts have not been disclosed but could be disclosed without legal restrictions;

- Identifying which contracts are still not being disclosed despite a legal mandate to disclose them.

- The MSG should then seek to understand current policies on contract disclosure. The MSG could undertake a review of existing policies on contract disclosure as reflected in the law, regulations or contracts. The review could include:

- The contracts regime in the country;

- The regulatory framework (e.g. which government entity is responsible for granting, implementing and monitoring extractive contracts? What are their roles and responsibilities?);

- A description of whether legislation, other policy documents or contractual stipulations prohibit disclosure of contracts and licenses;

- Documentation of the MSG’s discussion on what constitutes government policy on contract disclosures;

- Reforms underway (e.g. are confidentiality clauses still included in contracts that will be entered into after 1 January 2021? Are there opportunities to ensure that these clauses are no longer included in contracts that will be entered into after 1 January 2021?);

- Other laws and policies that could be used to support contract disclosure.

- The MSG should seek to address legal barriers. In doing so, it is recommended that the MSG considers the following:

- Where there are laws or contractual stipulations prohibiting disclosure, explore the option of voluntary disclosure by parties through the execution of waivers. The EITI Board has clarified that waivers could be accepted as interim measures when it is anticipated that addressing legal barriers permanently could take time.

- Agree a time-bound action plan for permanently addressing legal barriers and recommending policies for disclosure. These activities should seek to eliminate these barriers and ensure that all contracts and licenses entered into or amended from 1 January 2021 no longer contain these confidential stipulations or that laws requiring confidentiality are amended. This should be integrated into the EITI work plan.

- Discuss what the confidentiality clauses prohibit in practice and whether they apply to the disclosure of the contract itself. In some cases, confidentiality provisions are invoked without the stakeholders fully understanding the extent of their application. MSGs could facilitate a dialogue among relevant parties to reach a common understanding on the application of these provisions. In conducting these discussions, key points to consider include:

- The definition of “confidential information” often does not include the contract itself;

- Confidentiality clausesHideFor an overview of approaches to confidentiality, see Revenue Watch (2009), Contracts Confidential, pp. 23-32, might not be absolute. They could be addressed through waivers, where both parties agree to disclosure, where the host government requires disclosure, or where disclosure is demanded by company investors, company stock exchange listing requirements or the company’s home government;

- These clauses are sometimes time-bound, which means that confidentiality is not permanent.

The EITI Board has clarified that the redaction and publication of summaries of contracts are not acceptable even as interim measures under Requirement 2.4, because these could potentially create more suspicion and could slow down progress in addressing legal barriers. Because contracts contain many detailed and interlinked terms, publication of full-text documents is important to avoid misrepresentation, misunderstanding and mistrust that may arise when incomplete or inaccurate summaries of contract documents are produced.

Step 5: Actual disclosure of contracts

- Agree on a method for disclosure. The EITI Standard has no formal requirements on methods for contract disclosure, but public access in open formats is recommended. Different countries have various ways of publishing extractive contracts. Some have done so through dedicated platforms such as resourcecontracts.org (e.g. Philippines, Sierra Leone), while others disclose through government websites (e.g. Ghana, Mexico, Timor-Leste) or company websites.

In agreeing methods for disclosure, MSGs could consider the following:- Consider systematic disclosure of contracts through government websites as default practice to enable public access to the list of active contracts, the actual contracts and the annexes. MSGs are expected to systematically disclose data through government platforms by default. This approach strengthens the government’s implementation of a full contract disclosure policy and enables easier information-sharing across relevant government agencies.

Publication of contracts elsewhere (e.g. in EITI Reports or EITI websites, independent contract portals) are useful interim measures when the government is transitioning to systematic publication of contracts. In discussing systematic disclosure of contracts, MSGs should also consider the technical, financial and administrative resources needed to establish and update the government’s contract portal. MSGs could also look into whether contracts could be linked to other project-level information already being disclosed, such as payments or production or online cadasters, to facilitate use of contracts by stakeholders. - Ensure free access to disclosed contracts. While establishing and maintaining contract portals could require administrative costs, it is good practice to make contracts freely accessible. As a last resort, fees could be imposed as long as they are reasonable and not prohibitive. If fees are necessary at the initial stages of establishing a contracts database, MSGs are encouraged to consider a plan to enable free access in the long term.

- Develop and update the contracts database. This could entail:

- Identifying who is responsible for keeping track of and publishing newly executed contracts;

- Identifying who is responsible for keeping track of amendments and for publishing them. This responsibility includes keeping track of amendments of contracts executed after 1 January 2021 and publishing these amendments. It also includes keeping track of amendments of contracts executed before 1 January 2021 and publishing the full text of the original contract and the subsequent amendments;

- Conducting a periodic review on the comprehensiveness of disclosed contracts;

- Agreeing on a period within which new or amended contracts and amendments to contracts should be disclosed, where there is no government policy on when amendments should be disclosed;

- Using machine readable formats. Often, documents are in locked PDF files that a computer cannot read. Machine-readable formats make the process of using contracts much easier. For example, with a machine-readable contract, someone interested in knowing more about company royalties could conduct a keyword search of “royalties”, rather than reading through the contract in full;

- Collating all documents managed by different agencies. Full disclosure includes the complete range of contracts, annexes and amendments. In some countries, these documents may be held by different agencies within a government. For example, the main contract may be managed by the sector ministry, while environmental documents may be managed by an environmental protection agency. Bringing all these documents together in one place can make it easier for users to understand the big picture and find what they need;

- Organising documents according to the local legal framework. Each country has a standard range of contracts, annexes and amendments associated with each project. Organising documents according to these categories will make it easier for users to understand how documents relate to one another, and to find what they need.

- Consider systematic disclosure of contracts through government websites as default practice to enable public access to the list of active contracts, the actual contracts and the annexes. MSGs are expected to systematically disclose data through government platforms by default. This approach strengthens the government’s implementation of a full contract disclosure policy and enables easier information-sharing across relevant government agencies.

Mexico: Disclosing contracts through an online portal

Since 2013, Mexico’s petroleum regulator, the National Hydrocarbons Commission (CNH), has been hosting a platform on its website that discloses the full text of contracts and the procedures, practices and documentation of licensing and contract monitoring. Contracts are updated in real time as they are executed to ensure comprehensiveness. The platform allows users to see the changes within the contracts overtime, and explains the regulatory processes around contracting. It systematically discloses award processes, as well as information on the implementation of contractual provisions, including payments to government, production data and local content.

2. Ensure that full texts of contracts, all relevant annexes, addenda or riders and exploration contracts as agreed by the MSG are comprehensively disclosed. As previously noted, redacted contracts do not fully meet Requirement 2.4. MSGs could seek the attestation or confirmation of the parties that there are no omissions on the published version of the contract. The MSG could undertake spot checks, comparing published versions with original versions kept by the relevant government body.

3. Consider what features to add to increase access and comprehensibility of contracts. For example, annotations of contracts or explanation of some stipulations could be added by the MSG. Machine-readable formats could allow for key terms in the contract to be searchable. Summaries of contractual provisions could also be provided, along with links or related permits.

License regimes

For countries that follow license regimes (i.e. where agreements have standard stipulations as mandated by law), ensure that the MSG has evaluated whether there are deviations from standard stipulations that merit publication of individual licenses. If there are claims that these licenses have standard stipulations as mandated by law and that there are no deviations from such provisions, the onus is on the country to substantiate such claims. As clarified by the EITI Board, the MSG could consider the following approach:

- The MSG should document and evaluateHideIn doing so, the MSG could be guided by the following: (i) whether the obligations of contractors are defined in laws or defined in contracts; (ii) If defined in laws, whether these laws cover all terms of the agreement between the parties to the contract or there are stipulations that are left for the parties to negotiate; (iii) whether the same terms prescribed by laws exist in all contracts. the claim that there are no deviations;

- If the MSG concludes that all the terms of agreements in all contracts are governed by laws and that there are no deviations from these legal provisions in any of these contracts, it is sufficient for the country to publish only model contracts. Otherwise, the MSG should disclose individual contracts in line with Requirement 2.4;

- In making this decision, the MSG could consider whether non-disclosure would invite suspicion or erode public trust on the parties to the contract;

- To ensure that MSG decisions in this regard are not outdated, the MSG could consider undertaking the same review process for each license issued.

Dissemination and use of data

Contract transparency can promote public understanding, debate and reform. To harness the benefits of contract transparency, the MSG should endeavour to communicate disclosures to citizens and relevant stakeholders.To this end, the MSG can consider conducting capacity building activities to make sure that people understand what these documents mean and how they can be used and misused.

The MSG may also encourage stakeholders to use contracts by monitoring compliance, tracking changes to the legal framework, and scrutinising distribution of risk and reward to understand future scenarios.

How contracts disclosure can be used by government

Informing revenue projections

Entering into deals to extract natural resources often comes with the expectations on the project’s potential contribution to the economy. Disclosing the fiscal terms of the contract, including expected revenues at various stages of the project, could shed light on whether expectations on the project’s economic contribution are realistic. This could inform the government’s decision on whether fiscal terms should be revisited.

To facilitate this discussion, MSGs could undertake financial modelling using contract stipulations to forecast expected revenues from the project over a given period.

Mozambique: Projecting revenues to evaluate expectations

The government of Mozambique entered an Exploration and Production Concession Contract (EPCCs) with ENI known as the Coral South Floating LNG, the first natural gas project in the country. The project was expected to be a game-changer for the country’s economy, with forecasts assuming early exports, rapid expansion of production capacity and very high LNG prices.

Based on the terms of the contract disclosed by the government, an independent government revenue forecast was commissioned by Oxfam Mozambique. According to the report, “the model analyses the economics of the project, year-by-year, by integrating data on anticipated production volumes and production costs, varying LNG price scenarios, and the fiscal terms that determine how revenues will be allocated between costs, government revenue and company profit.” The analysis shows that “the government share of revenues, around 49% at a $70/barrel oil price, is relatively low and that the bulk of these revenues are generated late in the project life cycle, only starting in the 2030s.” It recommends that “Mozambique take measures to review the fiscal terms and ensure government capacity to monitor the projects to maximise revenue collection under those terms.”

How contracts disclosure can be used by civil society

Helping improve revenue collection

Contracts yield valuable information to communities who wish to see how revenue from their resources flows to regional or local governments. They can be analysed and used to help citizens understand and monitor performance on the obligations placed on companies, including measures to protect communities and the environment, make social payments, provide local employment or use local suppliers.

Having access to information on monetary obligations stipulated in contracts enables government officials and citizens to properly monitor whether companies are meeting these obligations. In some countries, various agencies tasked with collection of revenues do not know the legal and contractual basis for such payments, making their assessment of tax liabilities challenging. Contract disclosure addresses this by reducing information asymmetry among parties.

Civil society could play a role in raising awareness and improving comprehension of contractual stipulations by doing its own analysis of the terms of the contract through studies and engaging in discussions with government. One example is the approach taken by the Lebanese Oil and Gas Initiative (LOGI) to disseminate the findings of its financial modelling exercise through a video uploaded on their Facebook page to ensure wider reach.

Democratic Republic of the Congo: Clarifying fiscal terms to strengthen revenue collection

In 2011, the DRC government issued a decree mandating that extractive contracts should be published by the relevant ministry within 60 days from execution. Efforts by the DRC EITI to implement this policy led to the clarification of fiscal terms in contracts between foreign companies and SOEs, which often cover strategic reserves and large mining projects.

In 2020, the DRC EITI led an analysis of four contracts covering gold and diamond projects and identified red flags, including the failure to meet contractual obligations to SOEs in violation of the Mining Code and deviations with established public procurement procedures in selecting the companies. The absence of feasibility studies to confirm reserves was also highlighted. It is expected that these findings would lead to improvements in monitoring of revenues paid by extractive companies to SOEs, better follow-up of transfers of revenues from SOEs to the Treasury, and more public oversight over partnerships signed between extractive companies and the state.

How contracts disclosure can be used by industry

Explaining the terms of the contract to the public

Lack of public access to the contract could raise questions on the reasonableness of its terms. Some stipulations could be perceived as lopsided because of the highly technical nature of extractive contracts. Contract disclosure mitigates this risk by providing an opportunity for industry to explain the considerations behind fiscal terms, why deviations from model contracts are necessary, and why tax exemptions are granted.

Tanzania: Using contract disclosure to explain deviations from model contracts

Following the disclosure of the Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) over the Songo Songo Gas Field, Pan Energy explained the terms of the disclosed contract to describe how the government of Tanzania earns revenues from the project. It further described the company’s actual total contribution to government revenues which aligns with the contractual stipulations on fiscal terms, profit gas sharing ratios and computation of costs.

The company referred to the disclosed stipulations to explain deviations from the model PSA, including why royalties were not required, why an abandonment fund was not agreed, and the risk factors that were considered in agreeing on a maximum cost recovery rate that was higher than that stated in the model PSA. They illustrated how “protected gas” is accounted for as the company’s domestic obligation without a corresponding revenue. Disclosing the contract helped the company shed light on why the company has not paid Additional Profits Tax despite stipulations to do so, explaining that “the costs are such that profits have never reached the levels of investor returns whereby APT becomes applicable.”

Linking contract transparency with other national reforms

Contract disclosure complements other reforms in the extractive sector such as corruption mitigation, beneficial ownership transparency, and energy transition.

In Indonesia, the Publish What You Pay coalition has led discussions on how contract disclosure, open contracting and beneficial ownership complement each other to mitigate corruption by detecting potential conflicts of interest in the award of licenses and prevent collusion among companies in the bidding process.

In Sierra Leone, contract transparency is being used to enhance accountability and improve negotiations. The disclosure of a mining contract has prompted an investigation by the country’s Anti-Corruption Commission. The publication of a separate contract with the company SL Mining has helped government negotiations, specifically on terms related to resource mobilisation.

According to a report by Chatham House, the energy transition could challenge the assumptions underpinning the fiscal terms of the contract and the timeframe for production. Contract disclosure could facilitate an analysis of existing contracts to understand transition risks such as “substantial economic risks where the fossil fuel supply (and the infrastructure required to utilise it) becomes more expensive than clean alternatives.” This analysis could help governments asses how to mitigate these risks as it pursues reforms on energy transition.

Further resources

- EITI (2021), Policy brief: The case for contract transparency.

- ILSP, NRGI, OpenOil & VCC (2014), Mining Contracts: How to read and understand them.

- NRGI & Open Contracting Partnership (2018), Open Contracting for Oil, Gas and Mineral Rights: Shining a Light on Good Practice.

- OpenOil (2012), Oil Contracts.

The EITI International Secretariat has also compiled resources on contract disclosure online.