Republic of the Congo: Modelling EITI data to strengthen the government’s future oil revenues

Using financial modelling to examine the country’s fiscal regime, oil sales and potential oil revenues

The extractive industries are a bedrock of the Republic of the Congo’s economy, generating more than half of total government revenues. As a large oil producer in Africa, Congo has long faced public demands for greater transparency on the management of its oil wealth.

EITI reporting in the Republic of the Congo has generated a treasure trove of information. In 2013, the country began publishing oil production data for all licenses, and three years later it started disclosing data on all individual oil sales, as well as project costs for each license. It also discloses all its oil contracts in full.

These disclosures have enabled ITIE Congo to conduct an analysis of past trends and forecast potential future revenues based on various scenarios. Using financial modelling, a recent study, undertaken by R4D, looked at past and expected future payments from key oil projects as well as companies' oil sales, in order to promote an informed debate based on the analysis of EITI data and examine the effectiveness of Congo’s fiscal policies.

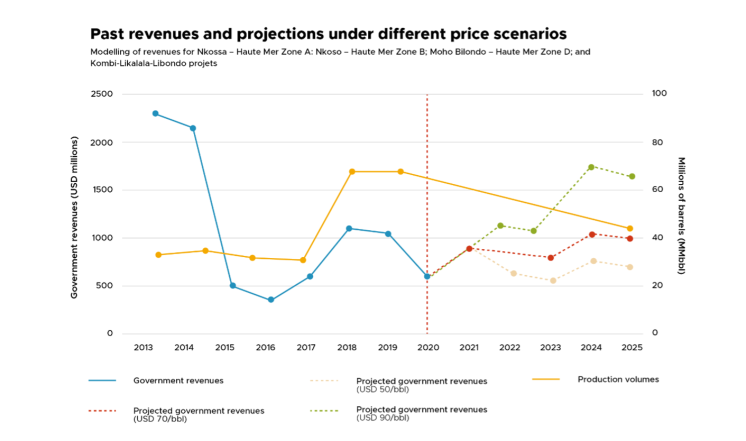

Charting past and future oil revenues

The analysis examines past and future revenues for four major projects using different price scenarios and accounting for the main parameters that influence the state’s share of revenues. The study found that, due to changes in the fiscal terms, government revenues from these four licenses are not expected to return to 2013 and 2014 levels, even under a high price scenario.

Between 2013 and 2019, oil prices fell from a high of around USD 100 per barrel to a low of around USD 40 per barrel. In the same period, however, production doubled and annual project revenues increased by about USD 1 billion per year. Yet annual revenues to the government decreased by more than USD 1 billion per year.

Why the decrease in government revenue?

Even if production growth compensated for declining oil prices, the study found that the government earned less due to its shrinking share of project revenues, which was scaled down from around 60% in 2013 to less than 30% in 2019. This decrease is attributable to renegotiations of terms in the oil contract related to what is called the “high price” instrument. This has seen an increase in the share of revenues going to the companies for their costs.

Simplifying fiscal terms

The study compared the fiscal terms of several production sharing contracts (PSCs) and oil contracts with those of other countries, including Angola, Ghana and Nigeria. To keep pace with the international oil market and encourage new investments, Congolese contracts have needed to be amended frequently. Over time, Congo’s fiscal regime has become increasingly complex, in large part to accommodate the “high price” instrument (“prix haut”) – a concept unique to Congo’s sector – which triggers an allocation of super profit oil and determines the value of cost oil.

Yet the comparative analysis demonstrates that the complexity in the Congolese system has not improved the performance of the fiscal regime and the terms have not proven to be durable. The study concludes that more traditional production sharing systems, with fewer fiscal instruments, perform better under a range of scenarios. It also shows that sharing profit oil based on a measure of profitability (for example by using an R-factor formula as in Nigeria, or a rate of return as in Angola), can support a more sustainable fiscal system without referencing a specific oil price.

Uncovering project costs

The study compared development costs for four Congolese projects with 44 offshore oil projects across the continent. The findings suggest that the costs for some of Congo’s projects are among the most expensive in the region. However, the underlying data was limited, and the findings are therefore not conclusive. A more detailed analysis of development costs, based on detailed cost claims by companies, could provide greater insight on the potential losses to government revenue from oil project expenditures.

Benchmarking oil sales and prices

Around 90% of Congolese crude oil sales are dominated by two blends (Djeno and Nkossa). Comparisons with corresponding crudes in Angola and Nigeria suggest that, while quality and shipping costs are on par, the Congolese blends sell at prices below their regional counterparts.

Furthermore, four companies – TEPC, Eni Congo, Chevron, and Hemla – sell their entitlements to affiliated companies, which constitute more than 66% of Djeno sales and more than 80% of Nkossa sales. According to the study, comparisons among companies selling Congolese crude suggest that TEPC, the largest seller of Djeno (47%) and a major seller of Nkossa (20%), sell at lower prices. This warrants further analysis of price differentials with regional crudes and among Congolese sellers, given the scale of revenues at stake.

The sale price of Congolese oil determines the division of production between the companies and the state. Specifically, a fiscal price is used in production sharing systems to determine the allocation of cost oil to companies.

According to the 2016 Hydrocarbon Code, the fiscal price must reflect market prices based on transactions between independent buyers and sellers. The study found that in practice, although only 13% of Djeno sales and less than 1% of Nkossa sales are between independent buyers and sellers (the state-owned enterprise SNPC’s sales are not considered), the monthly fiscal price was based on the reported realised sale price from all these affiliated private sales, with no further adjustments.

According to the study, when comparing realised sale prices with the monthly fiscal price, Eni Congo’s reported sales exert an upward influence on the fiscal price, while TEPC’s reported sales exert a downward influence. Given the importance of the fiscal price in the generation of government revenues, and the predominance of transactions between affiliated parties, Congo is advised to strengthen procedures to ensure that transactions reflect arms-length market prices. Furthermore, the study found that the national oil company, SNPC, tended to sell the government’s share of oil for a lower price than achieved by the private companies.

Next steps

Valuable lessons can be drawn from the findings of the study, which offers a data-driven steer for informing public debate on Congo’s fiscal regime. ITIE Congo recently held a workshop to present the findings of the study to representatives from government, SNPC, private companies and civil society – a welcome step to promote multi-stakeholder dialogue on the management of Congo’s extractive sector. Moving forward, there is scope for Congo to improve its disclosures and undertake routine revenue analysis and economic modelling, especially in view of uncertainties in future oil demand trajectories. The time is ripe for Congo to strengthen its policies and practices to ensure the country’s abundant oil endowments benefit its citizens, both today and for generations to come.

Contenido relacionado