EITI Requirements on beneficial ownership will help track origins and proceeds of corruption.

Indexes, for all their faults, are powerful communication tools for kick-starting policy discussion and change. In 1993 Transparency International put corruption on the map with the launch of the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), which the EITI has blogged about previously. Two years later, the Financial Times nominated 1995 as the Year of Corruption. Institutions, ranging from the World Bank, the UN and the OECD, followed suit in subsequent years with the adoption of a raft of anti-corruption regulations and measures.

Ever since, the publication of the CPI has been an important annual event, as the results are used by the media, politicians, investors, the public and others to assess countries’ levels of corruption.

Happily, several EITI countries have increased their scores in this year’s CPI rankings, including Mozambique, Mali, Mauritania and Trinidad and Tobago, all of which are mid- to low-ranking CPI countries. Other notable EITI countries - including Peru, Indonesia and Nigeria - have retained the same scores or merely increased/decreased by one point. Our OECD members - Norway, Germany, the UK and the US - remain near the top of the rankings.

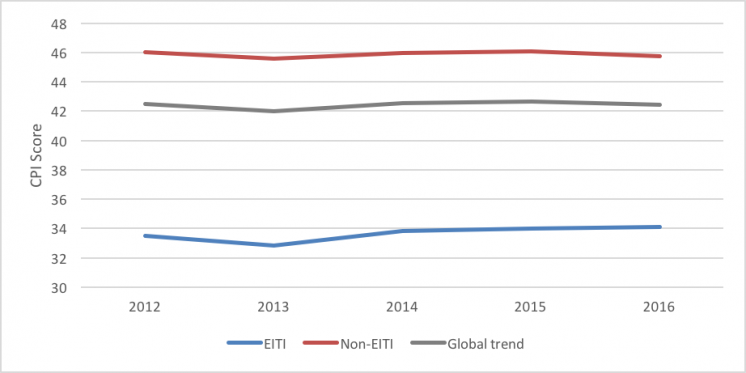

The graph below shows the CPI score for EITI and non-EITI countries since 2012, as well as the global average. EITI countries have made a slight gain in that time whereas the global trend has been slightly down. Overall, resource rich countries are ranked significantly lower than non-resource rich countries. However, as you can see, there hasn’t been much change in any groups in the past five years.

It will be interesting to see if that changes with the introduction of the EITI’s new requirements that companies disclose their beneficial owners. Beneficial ownership is linked to corruption because the proceeds of corruption are often transported out of countries through the use of anonymous companies whose ultimate beneficial owners remain hidden.

The CPI offers a snapshot of where corruption is perceived to occur, but this only tells half the story. At the London Corruption Summit last year, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, David Cameron, was overheard making an off-cuff remark about the attendance of the leaders of several ‘fantastically corrupt countries’, including Nigeria. However, the Archbishop of Canterbury was quick to point out that President Buhari of Nigeria had been elected on a platform to tackle corruption.

Many expected Buhari to be annoyed at the comment but, when asked if he would demand an apology, President Buhari responded by saying, “I’m not going to demand an apology from anyone, what I am demanding is the return of assets”. This is the other half of the corruption story: where the ill-gotten gains of corruption end up.

Leaders and officials of many of the countries ranked in the middle or at the bottom of the CPI have for many years been in discussion with the leading financial centres of the world to try and retrieve stolen assets. Unfortunately, these assets are often lost through the use of anonymous companies that hide their beneficial owners, making their recovery difficult, even when countries want to cooperate with one another on this issue. Nevertheless, there has been some success. Switzerland, a country famous for its banking secrecy, has returned some USD 500 million of stolen assets to Nigeria. A large amount, but no way near the estimated billions that are said to have gone missing over the decades.

Two years ago, the Tax Justice Network launched their Financial Secrecy Index (FSI) to shine a light on the countries where illicit money ends up. Together, the CPI and the FSI help indicate where illicit cash is flowing from and where it is ending up. Finding the companies that are dishonest is a huge challenge for government officials trying to crack down on corruption, particularly when companies with hidden ownership often look the same on paper as honest ones.

The extractive industries are at particular risk of corruption, given the high income associated with the sector. Over the past decade, the EITI has helped establish revenue transparency as a norm, and by 2020 EITI members will publish information on the beneficial owners of extractive companies. Publishing the real owners of extractive companies will make oversight and governance of the sector by government officials more effective and shed light on corrupt practices.

EITI countries will be amongst the first in the world to publish beneficial ownership data and it will be interesting to see how the CPI and FSI take this into account when assessing EITI countries. In other words: watch this space.