Wanted: Reputable mining investors in Sierra Leone

Wanted: Reputable mining investors in Sierra Leone

Lessons learned on how resource-constrained government agencies can improve integrity due diligence in managing mining licenses.

On the first anniversary of the Panama Papers, the National Minerals Agency (NMA) of Sierra Leone wants to know who its doing business with. The NMA is the government agency responsible for issuing mining licenses. Beny Steinmetz of Simandou fame is one such mining investor who has prompted the NMA to strengthen integrity due diligence. The Panama Papers revealed that the company Steinmetz was implicated in a complex chain of ownership of Koidu Holdings, Sierra Leone’s largest diamond mine.

Integrity due diligence means that the agency allocating the licenses, checks the reputation and track record of applicants. In doing so, the NMA hopes to weed out shady investors, and instead attract reputable companies to transform Sierra Leone’s mineral wealth. This ambition is echoed by the EITI’s call for disclosure of the ultimate owners of extractive companies, as well as the launch of a global register of beneficial owners by OpenOwnership.

Can a resource constrained country such as Sierra Leone reliably test the ‘integrity’ of mining investors?

The short answer is yes.

From October 2016 to March 2017, OpenOil was contracted by the Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, the German development agency, to work with the NMA to strengthen integrity due diligence in mining license management.

We found that prioritisation of resources, smart use of commercial products, and the ability to judge risk, enable the NMA to build a reasonably comprehensive picture of the integrity (or not) of potential investors. The expectation should not be that the NMA will always uncover the ultimate owner, or chase down the last dollar. The goal is to make informed decisions about who gets access to Sierra Leone’s natural resources.

Here are four lessons we learned that may be useful to other countries.

1. Prioritise mining license holders for ongoing integrity checks.

Developing country governments may not have enough staff to run integrity checks on all mining license holders. The NMA has four compliance staff to oversee 175 industrial mining licenses, and 2,078 trading licenses. Thankfully, not all license holders pose the same level of risk to the sector, or the wider economy. With the NMA, we developed a way of ‘triaging’ high-risk license holders for regular integrity checks. Regular integrity checks are important because the business profile of a license holder may change over time (for example through the sale of an asset).

Here’s what we did:

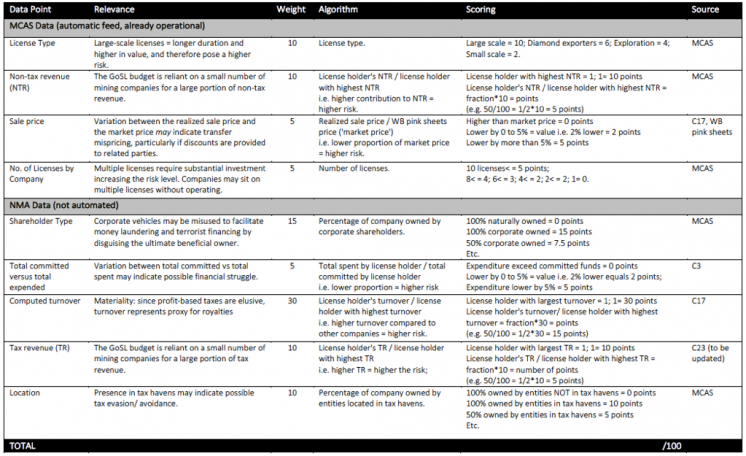

- First, we identified a set of risk indicators to measure all license holders against, based on data the NMA already collects via its Mining Cadastre System, which is available to the public through the online repository. One such risk indicator was the company’s contribution to total non-tax mining revenue.

- We gave each indicator a weight based on level of risk and reliability. For example, differences in sale price has been given less weight than license type, or presence in a low-tax jurisdiction, this is because there may be numerous legitimate reasons why a company’s sale price would be lower than the market price (e.g. differences in quality), making this indicator less highly correlated to risk.

Finally, we proposed an algorithm and scoring system for each indicator. The NMA is currently embedding these rules into its data analytics system. The result will be an automated list of 10-12 ‘watch list’ companies that require ongoing monitoring by NMA compliance staff.

The result is an automated system that generates a reasonable assessment of whether an existing mining license holder should be subject to ongoing integrity checks. Where the results appear incorrect, NMA staff can add or subtract ‘watch list’ companies.

Figure 1: integrity due diligence risk matrix

2. Commercial databases must be evaluated based on their specific application to the mining industry in the source country.

There may be limits to what open source data can deduce about an investor (e.g. where an investor is wholly owned by a company in a financial secrecy jurisdiction). The response to this challenge is usually that countries should invest in a commercial database from Reuters, or Bureau Van Djik. Yet, for many developing countries, including Sierra Leone, the cost of a database (anywhere from £5,000 to £25,000 per year) is hard to justify. To decide whether to invest in a subscription, government agencies should test the specific application of the database, to the mining industry in their country. In doing so, they should consider the following issues:

- The volume of mining companies that need monitoring. It may be that government would use only a fraction of the information on the database, despite paying for the whole resource;

- How much information the database contains on privately held companies, that is not publicly available from the local registry. The main reason to subscribe to a database is to aid due diligence of privately held companies. Yet, if the database is so scant that government would need to purchase extra data elsewhere (e.g. from a consultancy), it may not be a good investment;

- The extent to which the database uses public information to identify Politically Exposed Persons (PEPs). It may be that this information comes from media and news websites, company websites, and sanctions lists, all of which are publicly available;

- If the mining regulatory agency can establish the corporate ownership structure of mining investors i.e. identify all legal entities, directors, officers, shareholders etc. Some databases rely on users first knowing who the legal entities, and individuals involved are, to be able to search them. Developing countries should avoid databases that need a high level of prior knowledge of corporate structures.

A commercial database might be feasible if the EITI Secretariat and donor partners were to buy a collective subscription to license out to EITI implementing countries. This would be more cost effective, as well as help countries to implement the EITI Requirement on beneficial ownership.

3. Countries with a small number of mining investors may find purchasing one-off due diligence reports more cost effective than subscribing to a database.

If a government agency finds closed data necessary to conduct due diligence, a more cost effective and targeted solution is to buy one-off due diligence reports for specific mining license applicants. However, there are costs involved with this approach, therefore it should only be done for high-risk privately held companies (e.g. investors linked to state-owned enterprises), once the compliance team has exhausted all possible means of researching the company. An advantage to this approach is that it ‘kills two birds with one stone’ by getting a report, as well as receiving translated versions of company registry documents and media coverage if their source language is different from the agency’s.

Depending on the level of reporting, standard reports range between £100-£800. Very sophisticated reports can go up to $30,000. The cost comes down to how much source commentary, or ‘on-the-ground’ investigation is involved. In most cases, a standard due diligence report (company registration, adverse media results, sanctions and enforcements, basic information on directors and shareholders) should be enough for integrity checks, unless there are very serious concerns, or challenges to accessing company records.

For a country like Sierra Leone, where there is a handful of significant mining operations, buying one-off reports is more cost effective than subscribing to a database. This may not be the case for other countries with a more developed mining industry. However, even these countries may find it strategic to purchase one-off reports given databases can be variable on privately held companies.

4. Countries seeking disclosure of ultimate owners require a legal framework for beneficial ownership. In the meantime, government agencies can use other data points to inform integrity due diligence.

Whilst the NMA has ambitions to know who all the ultimate owners of companies are, as it stands, the law only requires disclosure of shareholders who own 5% or more of the issued share capital. There is a legal review currently taking place seeking to address other forms of ownership, which will likely result in comprehensive beneficial ownership legislation.

However, integrity due diligence does not have to wait until legal reform takes place. A lot can be deduced from information already collected by government agencies. For example, the NMA can already detect some PEPs issues based on the shareholder and related party data it collects from license applicants. Bearing in mind their current legal framework, government agencies should update existing disclosure requirements to maximise the information relevant to due diligence they are already entitled to.

Marker for a successful due diligence system

Effective due diligence of investors is critical to countering corruption, tax abuse, and criminal activity in the mining sector. Due diligence solutions should be simple and cost effective, considering the resources and capabilities of the government agency responsible for administering them. The mark of success is not a government agency knowing every legal and natural person involved in an investment. Rather, it is whether that agency can put forward an informed and reasoned view of the level of risk associated with an investor, such that a decision to grant a license (or not) can be made, and areas of concern flagged for ongoing monitoring.

Alexandra Readhead was the OpenOil Team Leader for the NMA due diligence project. She is an independent consultant in international taxation and extractive industries.

Image: Gravel waste from the mine towers over Koidu in eastern Sierra Leone. Photo: Cooper Inveen / GroundTruth (source page)